Firing in the “anagama” tunnel kiln

In Japan, the distinctive aesthetics of anagama kiln-fired pieces are highly sought after, and have been traditionally used since Sen no Rikyū in the 16th century as part of the chanoyu tea ceremony. The rusticity of the pieces fired using this technique perfectly corresponds to the aesthetic concepts of the tea ceremony.

The anagama kiln

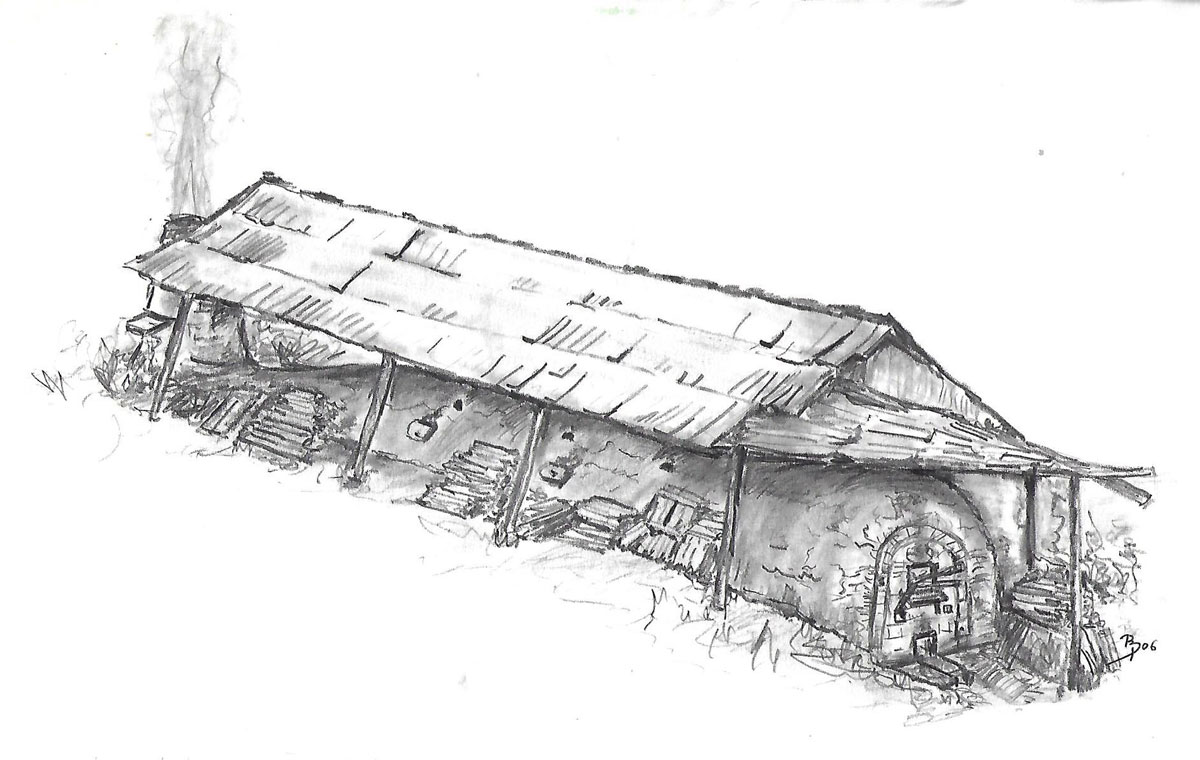

The anagama kiln is a semi-buried recumbent tunnel oven. These kilns are installed on slopes, which permits better draught and greater efficiency.

This is certainly the oldest form of oven for baking at high temperatures.

The anagama kiln imparts an exceptional character to the pieces that are fired in it. This is why Western ceramicists in North America and Europe continue to use this type of kiln with enthusiasm, despite the exhausting (yet fascinating!) experience inherent in these firings.

History

Inspired by Chinese and Korean kilns, the Japanese began to bake in underground kilns carved into slopes around the 5th century (the era of Sue ceramics).

These ancestors of anagama kilns made it possible to create a ceramic with an original aesthetic that is removed from overly-perfect Chinese ceramics.

In the 16th century, with the emergence of the aestheticism of the tea ceremony instituted by the great master Sen No Rikyū, this rustic ceramic with its irregular and imperfect forms corresponded to the esprit of wabi-cha (the simple and healthy tea style).

Tea bowls (chawan), cold water vases (mizusashi), tea pots (cha-ire), and serving dishes (shiho-zara) are all fired in these anagama kilns.

In Japan, there is a lexicon of natural effects of wood ash glaze from anagama kiln:

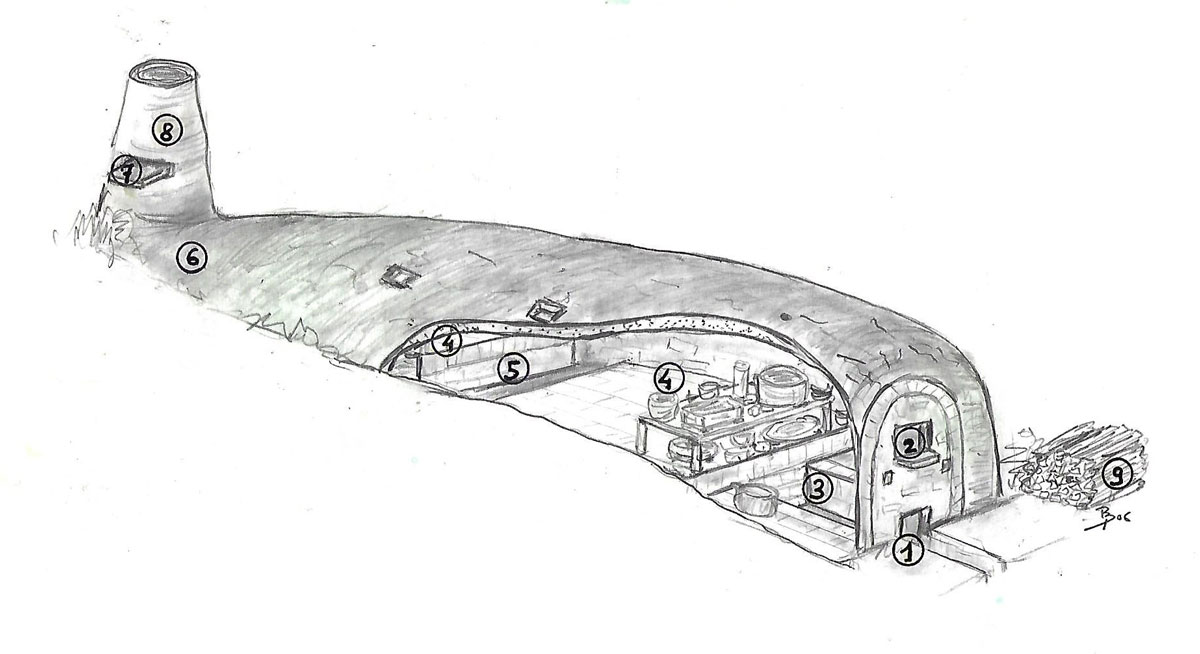

1: Lower firebox entrance.

2: Upper firebox entrance.

3: Principal firebox.

4: Pottery preparation space where the pieces to be fired are placed.

5: Firebox relay.

6: Compression chamber.

7: Flue dampers.

8: Chimney.

9: Dry and split wood.

Firing procedure

Anagama woodfire baking is long and tedious, but it is always a personal adventure. Indeed, this firing takes place as if it were an accelerated human life, with its joys, its doubts, its anxieties, its difficulties and its hopes.

To succeed in firing with these traditional tunnel kilns, several important factors must be taken into account:

-Preparation of the wood:

A good stock of split wood, cut to length, which has had three to four years to dry is necessary. Pine is the ideal fuel here, both for its flame and for the beauty of the natural ash covers that it produces.

-Loading the kiln:

The way in which ceramicists position their creations in the pottery preparation space will determine the effects that firing has on them.

During the loading process, the ceramicist must get a sense for the fire and anticipate its route between the pieces. The ceramicist must imagine the possible ash deposits that may be deposited on the ceramics. The ceramicist knows that the flames will always pass by the shortest path. Therefore, the ceramicist must create baffles between the pieces to make the flames weave and lengthen them as much as possible. Otherwise, it will not be possible to raise the temperature of the kiln to the level necessary for baking the stoneware pieces (1,320°C).

-Firing:

Next comes the actual firing process. Clear, cloudless days with a high atmospheric pressure are required.

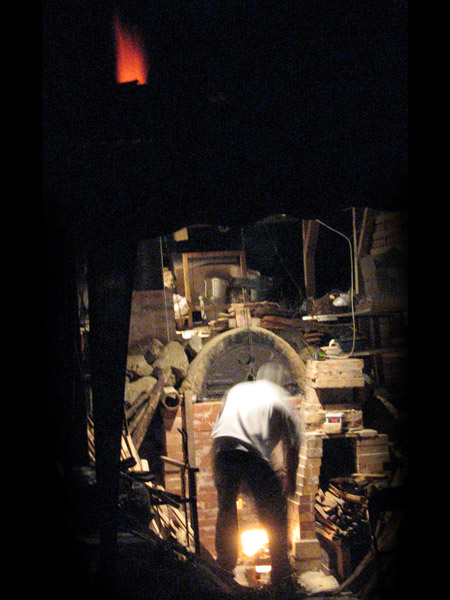

During the firing process, the human aspect is of primary importance. The kiln fireman must know how to listen to the oven, its needs and requirements. Throughout the firing process, he is obsessed with the rise in each degree of temperature, with eyes fixed upon the pyrometer indicating the inside temperature of the pottery space.

At times, he must be very active, providing large loads of wood to the mouth of the furnace and managing the oxygen supply as well as possible. In contrast, at other times, during seemingly endless stages, the kiln fireman must “feed the beast” without seeing the temperature rise by a single degree, which requires being patient and combative.

The temperature rise curve for this type of furnace is not regularly exponential: sometimes it rises, sometimes it falls, sometimes it stagnates. It’s all part of the game: you just have to accept that the oven is in control.

Starting at 1,100°C, it is necessary to alternate the oxidation (clear flame) and reduction phases (opaque flame with black smoke), in order to give substance to the workpieces.

At the end of the firing process, after 24 to 35 hours of hard work and four and a half cubic meters of wood consumed, we finish with a final heavy load. Then, the openings and the chimney are closed off and all the gaps are filled with cob; the oven is then like a big dragon roaring and giving off black smoke everywhere.

Now comes the slow cooling phase. During these four days of waiting, the temperature will gradually drop. Opening the kiln any earlier would be a guaranteed disaster.

After that comes the unloading: it is finally possible to contemplate the fruit of more than three months of work. There are always beautiful surprises and disappointments, but isn’t this the case with any creation, with any life story?

A video presentation of firing in an anagama kiln by Patrice Bongrand:

Whatever art you are passionate about, if you want to progress and delve into the essence of the matter, the regular practice of that art is demanding. Joy is not only to be found in the result, but also throughout the entire creative process.

In the end, the passing of time has its virtues, for it accompanies us in our work.

Search a product

Last products

-

Cha-ire N°Chir14

€100.00

Cha-ire N°Chir14

€100.00

-

Cha-ire N°Chir09

€90.00

Cha-ire N°Chir09

€90.00

-

Cha-ire N°Chir06

€55.00

Cha-ire N°Chir06

€55.00

-

Cha-ire N°Chir05

€55.00

Cha-ire N°Chir05

€55.00

-

Cha-ire N°Chir03

€70.00

Cha-ire N°Chir03

€70.00

Contact us

Feel free to contact us for any question: Contact page

Patrice Bongrand

Rua principal 124

Mosqueiros 2460-203

Alfeizérâo – PORTUGAL

Tél: 00 (351) 262 990 468

Tél: 00 (351) 964 244 110